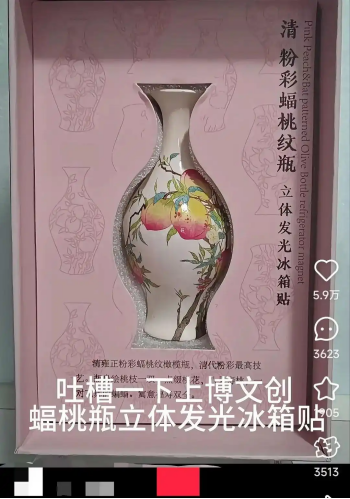

Recently, two cultural and creative products based on the Qing Dynasty’s Yongzheng Famille-Rose Bat-and-Peach Vase, housed in the Shanghai Museum, have sparked a heated online debate.

It began when a netizen claimed to have purchased a refrigerator magnet shaped like the vase at the cultural gift shop of the museum's East Wing. The magnet's "lighting function" and "hole in the base" were interpreted as an uncomfortable echo of the vase’s history when it was overseas — reportedly filled with dog feces and soil and repurposed as a lamp base. This prompted others to dig up images of a lamp designed using the same vase motif, with one commenter noting, “It’s been turned into a lamp again — the one thing it never wanted to be.”

The debate quickly escalated into polarized opinions. One side accused the designers of disrespecting history and mocking national trauma. The other side felt people were overreacting, noting that turning the vase into a lamp could also be seen as an appreciation of its beauty and functionality.

Is the vase's overseas journey necessarily a story of humiliation? Does its use as a lamp indicate disrespect? And why did the museum decide to make it light up in the first place? A journalist from Wenbo Headlines interviewed Shanghai Museum staff and cultural relics experts to explore these three key questions.

The Bat-and-Peach Vase is currently on display in a central case in the ceramics gallery on the second floor of the museum's East Wing. With its long neck, rounded shoulders, full peach motifs, and flying bats symbolizing good fortune, the vase represents the pinnacle of Qing-era Famille-Rose porcelain craftsmanship. According to Zhang Dong, a researcher at the museum's conservation department, the vase was purchased at auction in 2002 by Hong Kong collector Ms. Cheung Wing Chun for HKD 41.5 million and promptly donated to the Shanghai Museum.

Before that, it had been in the possession of the family of Ogden Reid, former U.S. Ambassador to Israel. How the vase left the Forbidden City and entered that family's hands remains a mystery. Because it was imperial porcelain from the Qing court, many netizens associated it with China’s era of national humiliation. However, researcher Chen Jie from the ceramics department noted that imperial porcelain left the Qing palace through many channels, including diplomatic gifts. Historical records show that Emperor Qianlong exchanged gifts with the British Macartney mission. Even during the Yongzheng reign, similar cultural exchanges took place.

Another controversy concerns how the vase was used as a lamp base during its 40-plus years in the Reid family's collection. According to family accounts, they considered drilling a hole for wiring but ultimately decided against it to avoid damaging the vase. To stabilize the piece — which had an unstable, olive-shaped body — they filled it with sand and newspaper. Because the family also had dogs, some netizens assumed the sand contained dog feces and saw this as a grave insult.

Peng Tao, head of the ceramics department at Shanghai Museum, responded: “The family clearly thought the vase was beautiful. It was kept in their New York home — there’s no evidence it was filled with dog feces.” He added that it's common in the history of East-West cultural exchange for foreign collectors to repurpose or embellish Chinese porcelain. Experts confirmed the vase was undamaged upon arrival at the museum.

Professor Liu Zhaohui from Fudan University explained that adapting Chinese porcelain for new uses has long been a global tradition. In the Middle East, Chinese porcelain was inlaid with gems and treated as treasure. In Europe, pieces were adapted to suit Western tastes and needs — for example, with metal fittings for durability and style. Similarly, the Qing court often modified Western enamelware or Japanese lacquerware to suit imperial preferences.

"Out of all the vases, why did the Bat-and-Peach Vase need to light up?" asked many online. A Shanghai Museum spokesperson explained that since the vase entered the collection, over 40 different creative products have been designed based on it — including scarves, notebooks, and thermos bottles. The table lamp version has been sold in the museum's gift shop for years. The light-up refrigerator magnet is a recent product, launched in response to the growing popularity of novelty magnets.

“This year, light-up, glitter, and spinning magnets have been top sellers. We developed nearly 100 designs based on artifacts — the Bat-and-Peach magnet is just one of them. The light enhances the ceramic’s translucency and luster,” the spokesperson said.

The museum emphasized that all creative product designs are made with historical respect and that they consulted the donor before releasing any items. They also noticed that many accounts criticizing the product were newly registered, repeatedly mentioned a certain video game, and used inflammatory language to provoke conflict and gain traffic. Some even attempted to redirect attention to sell their own related merchandise.

Shanghai Museum reaffirmed its commitment to the philosophy of "art in life, life as art." They will continue listening to public feedback and innovating to offer high-quality cultural products for modern lifestyles.

It’s widely acknowledged that modern Chinese history is marked by national trauma. Many of the country's heritage sites and relics were once desecrated. Countless cultural treasures were lost overseas. But does that mean people today should avoid visiting the Great Wall or the Forbidden City because of their painful past?

Remembering history should inspire national strength, not burden the present with emotional shackles. Arguing that cultural relics cannot be appreciated, modified, or creatively reused because of their tragic past is a form of rhetorical coercion disguised as respect.

Each repatriated relic has a dramatic story. Many, such as Autumn Letter, Bo Yuan Tie, Five Oxen Scroll by Han Huang, or the iconic Zodiac animal heads from the Old Summer Palace, have inspired new cultural products. These creations help bring ancient artifacts into contemporary life and are a key part of the national effort to “bring relics to life.”

The return of cultural relics also reflects China’s growing international influence. In recent years, the U.S. has returned 38 artifacts; the Western Zhou Feng Xing Shu Gui was recovered; seven columns from Yuanmingyuan were brought home. Since the 18th National Congress, 48 batches totaling 2,113 artifacts have returned to China.

These items represent more than sorrow — they are symbols of national revival. Rather than trapping them in a narrow, emotional narrative, we should see their return as a testament to China's resilience and rising global stature.

In today’s internet landscape, sensationalism, emotional rhetoric, and polarization are common. Basic facts can be distorted. Just because a relic becomes a light-up magnet doesn’t mean it’s being disrespected. If we resist extremism, extremism won’t dominate the discourse. If we don’t pander to traffic, reason won’t need to tread so lightly.

Let’s protect our cultural heritage together — not divide ourselves in its name.

Declaration: This article comes from CCTV.com.If copyright issues are involved, please contact us to delete.